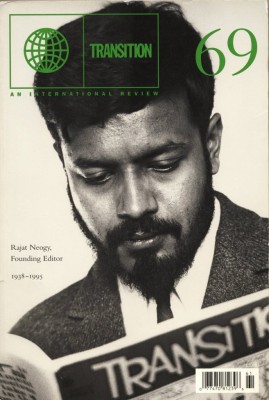

Rajat Neogy (1938-95)

Founder of Transition, the most daring and important literary and political journal of Africa’s 1960s.

Rajat Neogy was born in Kampala in 1938, the first of three children to Indian teachers who arrived in Uganda in 1937 and migrated to Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1960. He grew up in Kampala’s Asian community in a Bengali family, a minority in the East African Indian diaspora of majority Gujarati and Punjabi migrants. After attending the elite (mainly Goan) Kololo School in Kampala, he studied anthropology at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, married Charlotte Bystrom, a Swede, and worked briefly as a scriptwriter for the British Broadcasting Corporation.

On his return to Kampala in 1961 after the demise of his first marriage, he met and married Barbara Brown (née Lapchick), an American artist, former Ford and Vogue Magazine fashion model, daughter of the renowned US basketball player, Joe Lapchick, and the first director of the Nommo Art Gallery in Kampala. That year, at just 22 years of age, in the defining act of his short public life, Neogy founded the magazine, Transition. It would become the most daring and important literary and political journal of Africa’s 1960s and, after a revival in the African diaspora in the 1990s, continues to be a path-breaking pan-African global cultural magazine.

The birth of Transition

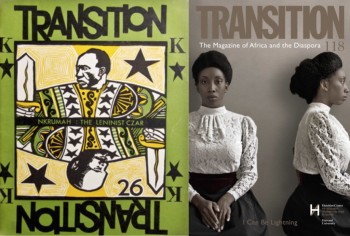

Neogy oversaw, as editor, the publication and growth of Transition, which ran for 50 issues: 37 published from Kampala (1961-1968) and 13 published from Accra, Ghana (1971-74). The final issues were edited by the Nigerian writer, Wole Soyinka, after Neogy’s resignation. At its height in 1967, 10,000 copies were printed each quarter; around half consumed across urban Africa and half overseas, particularly in Britain and the USA. Neogy was a central figure in the effervescent cultural and intellectual life of Kampala in the 1960s. He was a key sponsor and behind-the-scenes organiser of the landmark 1962 Makerere Conference for African Writers of English Expression, which attracted renowned literary figures from America and the Caribbean such as Langston Hughes and Arthur Drayton, alongside the cream of young African creative writing talent in Christopher Okigbo, J.P. Clark, Soyinka and a young James Ngugi (later Ngugi wa Thiong’o).

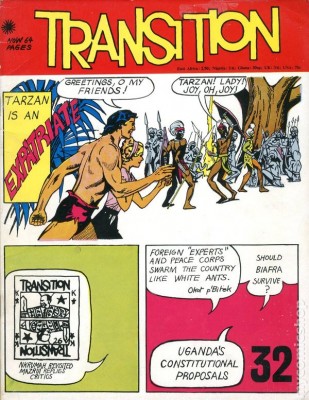

Transition would become the focal point for East African literary output and bold political commentary, which Neogy consciously placed alongside commissioned contributions by famous European and American, academics and activists such as M. Crawford Young and Martin Luther King. Neogy’s close friend in Kampala, the American writer Paul Theroux (at whose wedding Neogy was best man), decreed ‘Transition was more than a magazine; it was a movement, a vehicle for change.’

Obote’s ‘showdown with the intellectuals’

Transition became increasingly critical and iconoclastic of both neocolonialism and the predations of powerful African leaders. In 1968, the New York Times applauded that ‘a questing irreverence breathes out of every issue.’ As a result, in October 1968, Neogy was arrested on charges of sedition by Ugandan Prime Minister Milton Obote under state of emergency regulations after publishing an article by the opposition Bugandan MP, Abu Mayanja, which lambasted the authoritarian turn of the Ugandan state. Neogy was placed in solitary confinement in Luzira Prison and soon named an Amnesty International ‘Prisoner of Conscience’ for 1968 before a highly public trial – Obote’s ‘showdown with the intellectuals’ according to the British newspaper, the Financial Times.

At the trial, it emerged that Neogy had not officially renounced his UK citizenship, acquired legally by his Indian descent under the 1948 British Nationality Act, due to an oversight. Despite his birth in Kampala, he was not a Ugandan citizen. With the revelation of CIA funding for Transition through the Paris-based Congress for Cultural Freedom, something about which Neogy claimed ignorance, Obote castigated the foreign propagandism of Transition.

Neogy was eventually acquitted and released by the court but, disillusioned and brutalised by his imprisonment, briefly moved to Greece with Barbara and soon took Transition to Accra, Ghana, in 1971. Neogy exiled himself to the USA after the demise of Transition in 1974 first to New York and, in 1976, to San Francisco. He died, impoverished, in 1995. His journal was revived in the African diaspora at Harvard University by Henry Louis Gates Jr. just before Neogy’s passing, where it remains to this day.

Neogy's Kampala and the world

Neogy was both a man of Kampala and a man of the world, and it was this interface of the local and the global that was the cosmopolitan essence of Transition, as well as the cause of its demise. His global life was one of personal connections forged through Transition, East African cultural institutions, the bars of Kampala and his numerous travels to the US and Europe. He forged local friendships with leading Ugandan cultural figures such as the Acholi poet Okot p’Bitek and Makerere political scientist Ali Mazrui, both of whom wrote extensively and outspokenly for Transition in the mid-1960s.

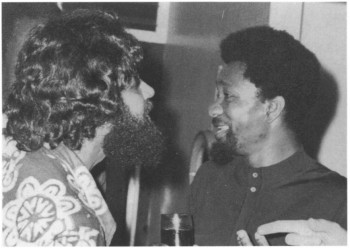

Neogy was equally at home in the salons of metropolitan New York, where he made the acquaintance of American Beat poet, Allen Ginsberg, in 1965. He plugged Transition into African-American civil rights activism with input from James Baldwin in 1964, while the brutalities of apartheid South Africa were rarely out of Transition’s pages through relationships with writers such as Dennis Brutus and Nadine Gordimer.

The controversies of the Congress for Cultural Freedom

Neogy’s institutionalised globalism was shaped by another South African, the exiled author Ezekiel (Iater Es’kia) Mphahlele. Financial precarity marked Transition’s early years, with Neogy often funding publication himself when advertising revenue from local East African Asian businesses dried up. From 1964, Mphahlele offered grants to Neogy from the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), initially a Euro-American cold war institution founded in 1950 which aimed to combat the international cultural influence of the Soviet Union, and which sponsored numerous liberal magazines, writers and artists throughout Europe, Africa and Asia to this end. Mphahlele had briefly run the Chemchemi Cultural Centre in Nairobi after a sojourn with the Mbari Cultural Centre in Ibadan, Nigeria, before his recruitment as African Director of the CCF in Paris.

Though such literary networks he made he acquaintance of Neogy, a rising star of African cultural curation and production. Modest CCF sponsorship enabled the consolidation and expansion of Neogy’s endeavours. The CCF network opened up Neogy to new avenues of internationalist possibility and affinity. Transition worked closely with Black Orpheus, the magazine of the CCF-sponsored Nigerian Mbari Writers’ group in Nigeria. Africa’s most anthologised poet, Okigbo, who trained at Mbari, became West Africa correspondent to Transition. Such convivial West African relations led to the re-location of Transition to Ghana after the Obote affair. It drove Soyinka, who also worked with Mbari and wrote repeatedly for the magazine in the halcyon days of the 1960s, to step in as editor when an unstable Neogy, his close friend, was no longer able to act as editor from 1974.

But tensions also emerged in Transition’s relations with West Africa given Neogy’s irreverent criticality. Mphahlele, who also arrived in East Africa to run Chemchemi from Mbari in Nigeria, joined Neogy in dismissing notions of negritude as productive tools of African decolonisation, to the consternation of several pan-Africanists in West Africa and the US, such as the African-American literary scholar and former CCF Africa Director, Mercer Cook, who later became America’s premier ambassador to Francophone Africa.

The CCF also plugged Transition into the London-based Transcription Centre, a gathering place and broadcaster for African writers run by an ex-BBC journalist, Dennis Duerden. Neogy travelled to the UK, where he had studied at university and married for the first time, to contribute to its programming and where he met travelling and exiled African writers, such as Bloke Modisane from South Africa, who wrote for Transition about anti-apartheid and pan-African brotherhood.

Endings

But the CCF also proved Transition’s Achilles Heel. In 1967, the revelation that the CCF was funded in part by the CIA through the front of the philanthropic Farfield Foundation, sparked outrage in Uganda and throughout sites of CCF activity across the decolonising world. Neogy expressed shock at the news of this scandal, claimed that the CCF never attempted to influence editorial decisions and that no-one working with Transition was aware of any CIA connection.

Transition was effectively dead and Neogy’s choice of final destination for exile – the US – underlined his global connections and provided the location for his tragic end. As Nigerian literary critic Michael Echureo later concluded, Neogy’s ‘Africa was not Africa at all’ and ‘that Transition was doing an ostensibly good job of liberation made the irony of the situation particularly painful.’ The local and the global, a continuum for Neogy, were mutually exclusive for Obote.

Archives and online sources

- Transition Magazine archive: https://www.jstor.org/journal/transition

- Makerere University Archive, Kampala, Uganda

- Uganda National Archives, Kampala, Uganda

- Kenyan National Archives, Nairobi, Kenya

- The International Association for Cultural Freedom Archive, Chicago, USA

- The ‘Transcription Centre’, ‘Bernt Lindfors’ and ‘Research in African Literatures’ collections at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas-at-Austin, USA

- The National Archives, London, UK

Further reading

- Rajat Neogy, ‘Do Magazines Culture?’ Transition editorial, volume 24 (1966)

- African Writers’ Club recordings (online in British Library and New York Public Library): https://sounds.bl.uk/Arts-literature-and-performance/African-Writers-Club

- Michael J. Echureo, ‘From Transition to Transition’, Research in African Literatures, 22, 4 (1991)

- Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Birth of a Dreamweaver. A Writer’s Awakening (New York, The New Press, 2016)

- Bernard Tabaire, ‘The Press and Political Repression in Uganda: Back to the Future?’, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 1, 2, (2007)

- Paul Theroux, ‘Rajat Neogy: Obituary’, The Independent, London, 15 January 1996

- Peter Benson, Black Orpheus, Transition and Modern Cultural Awakening in Africa (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986)

- Peter Kalliney, Modernism in a Global Context (London: Bloomsbury, 2016)