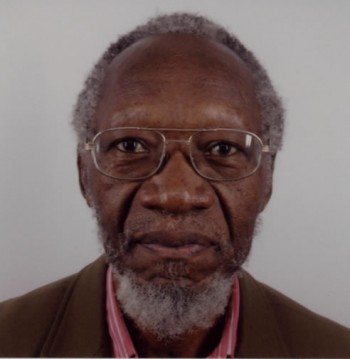

Hilary Boniface Ng'weno (1938-2021)

The first Kenyan editor-in-chief of the Nation newspaper group

Ng’weno is a critically important figure in postcolonial Kenyan history. His life is a reminder of how important the press has been to shaping public debate. Many biographies about Kenyan political leaders have been given special treatment over the past 40-50 years. However, this biography hopes to offer similar treatment to the role of press in shaping political debate.

Hilary Boniface Ng’weno, born on 28 June 1938 in Nairobi, was raised in Muthurwa, a place where his father worked for East African Railways. From St. Peter Cleavers, a place where he began his primary education, he joined Mang’u High School, before studying Physics and Mathematics at Harvard University in the USA, where he married Fleur Arabelle, a French holder of a BSC degree in conservation and former editor of Rainbow magazine. A father of two daughters Amolo and Bettina, Hilary Ng’weno is also considered the father of journalism in Kenya.

The Journey

In spite of his science-oriented studies, it was at Harvard University that Ng’weno, established, shaped and sharpened his journalism career. As a student, he began writing cyclostyled newsletters, a beginning of his consciousness of racial relationships in the 1960s. On his return to Kenya in 1962, Ng’weno became a reporter, feature writer and columnist with Daily Nation newspaper. Barely two years into his journalism career, at just 26 years of age, Ng’weno became the first indigenous Kenyan editor-in-chief of the Nation Group of newspapers, on 1 June 1964, succeeding Graham Rees. Perhaps his Harvard background, where it appears he met the Aga Khan, the founder of Nation Group, gave him an edge in this young company.

It was during his stint at the Nation that Kenya’s contribution within international press circles was visible. Ng’weno was among the chief speakers at 14th Annual General Assembly of the International Press Institute held in 1965 at Grosvenor House, London, joining British leaders and press figures like Lord Shawcross, Harold Wilson and Cecil King, alongside other leading press figures from Africa, including Enahoro Odinge, Gabriel Makoso and Herbert Unegbu. He delivered a speech on Press Freedom and its threats, and this defined his path in journalism. After the London trip, he quit the Nation in May 1965 and he became a freelance journalist, a platform he used to comment on global events. Re-establishing his global links, Ng’weno joined Harvard University for a second time as a Fellow of Harvard Centre for International Affairs (1968-69), and studied, through a Ford Foundation fellowship, film production and television at Brandeis University USA (1969-70).

His Tenets in Journalism

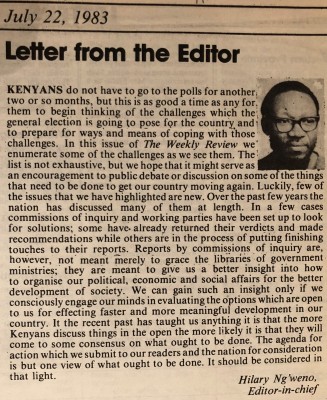

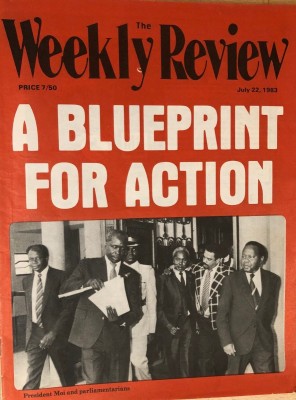

Ng’weno’s criticism of Eurocentric approaches might have been an influence of Harvard, a place he not only cyclostyled newsletters to African students in the US but also connected with the Aga Khan, the founder of Nation Media Group in Kenya. As part of his presentation during the 14th Annual General Assembly of the International Press Institute of 1965, Ng’weno advocated for press freedom, and identified three threats to press freedom as: state, courts and ownership or control by expatriates. On his second return to Kenya, Ng’weno launched his own newspaper, The Weekly Review (WR) in February 1975 in a bid to exercise press freedom he had envisioned in 1965. The WR became part of his larger company, Stellascope Ltd, a home to other publications, as a chief editor, including Rainbow (September 1977), Joe magazine, Financial Review, Sports Magazine and Business World. The WR embodied his skepticism of foreign owned newspapers. He felt that foreign ownership of the press promoted Eurocentric concerns, instead of offering an African view of socio-political realities in independent African countries.

He therefore construed that the only newspapers, Nation and Standard, which were owned by expatriates and foreigners, curtailed press freedoms and lacked ‘comprehensive sufficient background information and analysis of weekly events’ within the local realms. Ng’weno’s perception of free press was commingled within the WR. Apart from print media, Ng’weno worked with Kenya Broadcasting Cooperation in 1972, Esso Standard (East Africa) Limited and has also produced documentary films like ‘Makers of the Nation’. He is a recipient of a Rockefeller Award (1977) due to his contribution to journalism. His early connections shaped his path towards the struggle for press freedom.

Prophetic Journalism

Apart from chronicling the political environment of independent Kenya and her global connections, Ng’weno revisits the ideas and hopes of independence. By focusing on the past enthusiasm on attainment of independence, Ng’weno comments on disillusioned Kenya, making reference to Kenya’s contribution and influence on global connections. In ‘A Letter from Kenya’ he acknowledges all the dignitaries that attended the midnight 11-12 December 1963 Uhuru celebrations. Among the dignitaries, from Africa, were delegates from Ghana, Nigeria, Southern Rhodesia, and Tanzania: from overseas were delegations from China, Britain, USA, India, Pakistan and Israel. These were portrayals (and symbols) of the global contacts of the new state and at the same time mirrored the global figure of Ng’weno.

Due to his racial awareness as a student in America, Ng’weno blames expatriates for the grim artistic scene in Africa. In ‘Letter from Nairobi’, he highlights that East African arts were dominated by expatriates like Blixen, Hemingway and Ruark and that theatre and the Kenya Film Society were in the hands of foreigners. As early as 1970 Ng’weno, in prophetic-like journalism, singles out the would-be great literary icons within East Africa when he acknowledges, in the letter, African artists, among them writers including, from Kenya, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Grace Ogot, Rebecca Njau and Kudlip Sondhi (of Asian origin); from Uganda, Okot p’Bitek; and, from Tanzania, Walter Bgoya. In paintings, he applauded Eli Kyeyune, from Uganda, Louis Mwaniki from Kenya and Sam Ntiro from Tanzania as the best within East Africa. As a product of his global contacts, within the East African region, Ng’weno served as director of Chemchemi journal (initiated by a South African writer Ezekiel Mpahlele in 1964), chairman of Paa-ya-Paa Gallery. Ng’weno’s global contact draws his attention at the disappearance of old artistic traditions, traditions which would have equaled the ones in Arabia and Persia. Indeed Ng’weno, through the WR and his global contacts, transformed the public discourse on myriad issues in journalism. For instance, in the 14 July 1975 issue, Ng’weno lauds East Africa’s cordial relationship, between Uganda and Kenya in particular.

Despite his mild criticism of African governments, he maintained cordial relationships with the governments of the time, a quality attained at Harvard, a foreign place, but where he cyclostyled newsletters to African students. He occupied the middle ground and urged both government and its critics to lower their voices ‘a little so as to hear one another better’. However, this does not mean that political concerns featured less. In fact, the WR was dubbed a political magazine, corroborating its initial purpose to give a ‘comprehensive, unbiased and free interpretation of the many occurrences’. Among the occurrences are liberation heroes in Kenya’s history including Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, Achieng Aneko, Paul Ngei, Bildad Kaggia, Fred Kubai, Tom Mboya, and Kungu Karumba. This candid purpose kept the WR in circulation surviving, sometimes, the turbulent political moments of Moi regime (1978-2002). Perhaps, aware of the WR as a platform for knowledge and opinion (in politics), KANU bought Stellascope Ltd and Nairobi Times in 1983. In 1993 and 1999 he was the Chairman of Kenya Wildlife Service and member of Kenya Revenue Authority respectively, which were perceived as political appointments. Incidentally, in 1999 the WR wound up its publications.

Ng’weno’s global influence was two-fold. First, it ignited his African racial consciousness while at the same time plunged him into journalism. Secondly, global links transformed his perception of local politics and, in equal measure, he used these links as a platform for voicing local politics. Even though the WR closed down in 1999, it enshrined places that Hilary Boniface Ng’weno traversed as a student at Harvard University, and in his career as a journalist. Today, Ng’weno is considered as the father of, and an icon in, journalism in Kenya and Africa.

Relevant archives and online sources

Daily Nation

The Nation Centre library, Nairobi, Kenya

Transition

The Weekly Review

B. Lindfors interview with Hilary Ng'weno (1976), published in The African Book Publishing Record, Volume 5, Issue 3, https://doi.org/10.1515/abpr.1979.5.3.157

Further reading

T. Hopkinson, ‘A New Age of Newspapers in Africa’, Transition (1965), pp.38-40.

D. Makali, ‘From Gandfly to (just) a fly’, The Nairobi Law (January 1996), pp.8-9, 22.

Phoebe Musandu, Pressing Interests: The Agenda and Influence of a Colonial East African Newspaper Sector (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2018).

P. Ochieng, ‘Editorial Pontiffs’, in DN: 50 Golden Years (Nairobi: Nation Media Group, 2010)