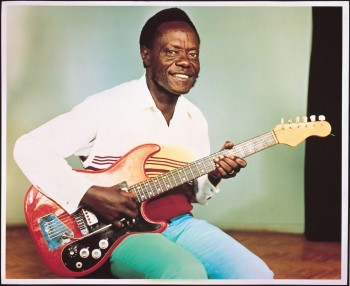

Daniel Owino Misiani (1940-2006)

The father of Benga music, taking multilingual lyrics to a global audience

Daniel Owino Misiani was born 22nd February 1940 in a village called Nyamagong near Shirati in the Mara region of Tanzania, near the Kenyan border. Misiani enjoyed a childhood of playing and singing in Luo in school and church choirs, and as a teen he played percussion in a local acoustic group.

His parents, however, on religious grounds disapproved of him pursuing a musical career, and Misiani’s first guitar was destroyed by his deeply devout Christian father. Irrespective, Misiani pursued a career in music and travelled around Tanzania and Kenya. His music career had humble origins as a travelling guitarist, playing at funerals, social gatherings and bars in the Luo homeland of Kenya’s Nyanza province. In 1964 he settled in Nairobi.

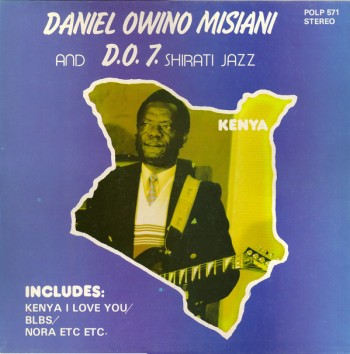

In Nairobi, Misiani drew inspiration from Luo traditional music and began to pioneer the benga genre, replacing the traditional nyatiti with electric guitars, retaining the fast tempos he had enjoyed at home. Inspired by the success of Nairobi-based musicians such as Daudi Kabaka, Misiani made his first electric guitar recordings in 1965. Soon after, he formed a band to record under, named the Shirati Luo Voice (later to become Orchestra D.O.7, and in 1975: Shirati Jazz).

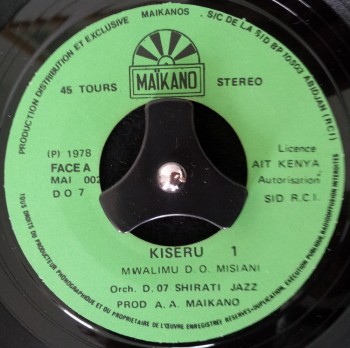

Shirati Jazz rose to the peak of its fame in the mid 1970s releasing an endless string of 45 rpm seven-inch singles such as Piny Lichina, Kiseru and Simon Agira, recording these various songs in Luo and Swahili. These were all produced under a variety of different labels, the most significant being Kanindo, Hundwe, Sunguru and Kung Fu.

Political dissent and satire

D.O. Misiani came to criticise the former Presidents of Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta, Daniel arap Moi and Mwai Kibaki during their leaderships of the country. Whereas the government sponsored choirs which composed music that helped celebrate the postcolonial state and maintain the status quo, musicians such as Misiani challenged these ideas. In his songs he called upon the presidents to answer controversial topics. During the early 1970s, in the song Kalamindi, Misiani criticised Kenyatta’s development policy which he perceived to perpetuate class and regional inequalities.

During the struggle for multiparty democracy in Kenya after the death of the then Foreign Minister Robert Ouko, Misiani was extradited by Moi’s government for ‘fuelling discontent’ in his music. After the December 2002 elections in Kenya, Misiani was arrested after releasing Bim men Bim (a baboon will remain a baboon). His song was perceived as an anti-government jibe which allegedly suggested that as Kibaki had been in Moi’s Government as Vice President he would not bring much change.

Misiani took an interest in political issues across the world, including coups, assassinations and ethnic conflicts. The subjects of his songs included events in Kenya, Congo, Egypt, South Africa, Somalia and Liberia. Misiani scorned leaders such as Idi Amin and had no problem in ridiculing leaders in Africa and across the world. In the song Wayuak ni Piny (We cry for the world) Misiani sang about the Iraq war and criticised George Bush for ruining the lives of Iraqis. He said that: “I just sing about what is happening and if this offends some people, I can do little about it. What is wrong with singing about what’s going wrong in our society?"

Taking Benga to the Global Market

Under Misiani’s musicianship Benga came to be a distinguished genre, and by the 70s other musicians alongside Misiani took it to a global stage. In particular, Misiani’s tracks ‘Harusi ya MK’, ‘Lala Salama’ and ‘Amka Salama’, had a wide public appeal and helped take the genre to the national and international market. The countries of Eastern and Central Africa, including Tanzania, Uganda and the DRC have all at one time or another heavily consumed Benga music either by accessing vinyl records or through seeing the visiting musicians themselves. Misiani often travelled around to perform, particularly in Tanzania.

Benga also became popular in spaces as far away as Zimbabwe and South Africa. Supposedly the most popular dance music in Zimbabwe was Benga, the popularity owing to the selling of records produced in Kenya. In Zimbabwe, Benga came to take a new name: Kanindo (named after a prolific Benga producer in Kenya who had produced many of Misiani’s tracks). Kanindo came to be a household name in Zimbabwe. What many Zimbabweans perhaps did not realise was that Kanindo was neither an artist nor the name of Benga but in fact the producer whose name simply appeared on the record sleeves. Through Zimbabweans, Benga came to take on a diasporic identity of itself as migrating Zimbabweans took Kenyan Benga music with them across the continent and beyond. In 2004, Misiani headlined a very brief US tour.

Death and Legacy

Misiani died in a road accident near his home in Kisumu on 17 May 2006. He was mourned across East Africa, but particularly by Kenyans who insisted he ought to be buried in Kenya instead of where he was born in Tanzania. Highlighting Misiani’s political engagement, former Prime Minister and leader of CORD Raila Odinga eulogised Misiani, stating: “Misiani’s death is a big blow to Luo-land and all progressive voices of this country. Misiani spoke for the voiceless not only in Luo Nyanza, but entire Africa. I have lost an advisor, inspiration and supporter.”

Beatrice Owino, Misiani’s wife, still leads the band Shirati Jazz, and said the following after his death: ‘‘Misiani’s fans and the band still owe a lot of respect to him because of his un-matched talent and wisdom in his career as a musician. We do not have an option but to follow his footsteps as a band.”

While Misiani was clearly a popular musician in Kenya, he also was successful in bringing Benga to a global market, with spaces in Central, Eastern and Southern Africa all dancing to the same Benga beats at some point in the late twentieth century. His personal engagement with global and domestic politics became manifest in his music, highlighting that he was part of a politically aware class of musicians during the 1970s and 1980s.

While figures such as Misiani may be overlooked when thinking of ‘global lives’, it is clear that he was part of a fabric of a globally connected Africa. Within the region of East Africa, and the continent he was particularly visible (and remains so) but less so beyond these networks. Perhaps the reason that Southern African jazz and reggae musicians and West African blues musicians have enjoyed more attention globally is that their genres have been appreciated on a more international (trans-Atlantic) market than Benga, which has enjoyed particular interest mainly within Africa. Using music could offer an especially imaginative way to think about intra-African connections.

Archives and online sources

The Nation

Further reading

I. Eagleson, ‘The King of History: Classic 1970s Beats from Kenya’, African Music: Journal of the International Library of African Music, Vol. 9, no. 1 (2011).

Joseph Muleka, ‘Pioneering a Pop Musical Idiom: Fifty Years of the Benga Lyrics in Kenya’,

Journal of Arts & Humanities, Volume 07, Issue 11 (2018).

Kimani Njogu and Hervé Maupeu (eds), Songs and Politics in Eastern Africa (Mkuki na Nyota Publishers, 2007).

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/daniel-owino-misiani-mn0000674710/biography