Boloki Chango Machyo W’Obanda (1927-2013)

A Ugandan public intellectual, between East African pan-Africanism and local politics

Ugandan Marxist and public intellectual, Machyo spent a part of his early life outside of East Africa, more connected to pan-African and international socialist circles abroad than to Ugandan party politics. However, in his later life he became increasingly involved in local and then national politics in Uganda. This specific political trajectory was interwoven with Machyo’s intellectual life.

Machyo was born in 1927 in Uganda’s Busia district, near the Kenyan border. After school there he trained at the Survey Training School in Entebbe, the colonial capital, and qualified as a land surveyor.

From student mobility to the president’s office

In 1956, aged 29, Machyo travelled with his wife Akumu Rose Nang’anda to the United States, where they spent a year with Moral Re-Armament, a spiritual movement that during the 1950s invited young people from East and Central Africa to their centres where they preached an anticommunist and multiracialist doctrine. It seems that in fact Machyo actually made contacts with the American Communist Party, and became an atheist – the invitation was also a way to get a passport.

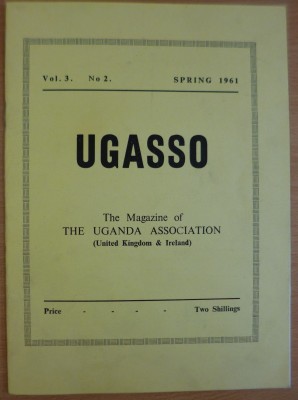

After his year in the US, in 1957, Machyo was awarded a Bukedi local government scholarship to study in London. There he became heavily involved in the Uganda Students Association, notably editing their magazine Ugasso, prior to Ateker Ejalu. He soon joined the Committee of African Organisations, which was the first African-led pan-African anticolonial organisation in London, formed by Abu Mayanja, a fellow Ugandan (who had also stayed with Moral Re-Armament) together with a Nigerian, Alao Bashorun, and Dennis Phombeah, a member of Julius Nyerere’s Tanganyika African National Union.

Machyo stayed in London for seven years, returning to Uganda shortly after the country won independence. He was employed at Makerere University as a resident tutor, based in Mbale. He was also working for the Uganda Development Corporation and travelled extensively in this capacity. However, he devoted much of his time to local politics, specifically lobbying around district boundaries in Eastern Uganda. He was part of the radical breakaway wing of Milton Obote’s Uganda Peoples Congress, under John Kakonge, and became involved in Yoweri Museveni’s formation of the Uganda Patriotic Movement and then National Resistance Movement. Thus, he moved from the fringes of mainstream politics to the very centre, spending the final years of his life as Presidential Advisor.

Overlapping networks and East African pan-Africanism in London

(courtesy of Peter Obanda Wanyama)

Archival documents found in Nairobi nuance this political trajectory, revealing a certain continuity of political thought and a complexity of pan-African and regional sympathies. In 1959 he sent a letter to East African friends and contacts in London. Machyo had just joined the Committee of African Organisations, mentioned above, but in this letter he insisted on the need for a separate East African organisation, given the strength of the famous West African students Union in London. This speaks to some of the dynamics of pan-Africanism and regional groupings during the period of decolonisation. Machyo felt that West Africa already had a lot of publicity after the independence of Ghana and Nkrumah’s pan-African conferences during 1958, he said there was a need to ‘furnish true and accurate information about our countries to those who may seek it’. Indeed, Machyo went on to publish several pamphlets, one under his own ‘Africana Study Group’. It is important to note that Machyo defined East Africa broadly, including Ethiopia, Mozambique, Zambia, and Malawi. The photo below suggests the extent to which East African networks – not only Ugandan or broadly pan-African – were important to Machyo’s time in London. In this context, networks of writers like Okot p’Bitek overlapped with those of trade unionists like Tom Mboya. When Machyo returned to teach at Makerere, some of these regional networks would have been strengthened, while others fell away.

Cold War positioning and African socialism

However, in different forums across the Cold War world, Machyo’s emphasis on student politics and regional identity were muted. A speech that Machyo made at the meeting of the World Federation of Democratic Youth (a Soviet-sponsored organisation) in Warsaw in 1962 can also be found in Nairobi. In it, Machyo emphasised the shared plight of African students and workers, and the need to dissolve the divide between Francophone and Anglophone students, and between those studying East and West of the ‘iron curtain’ – he was involved in organising an African student conference in Belgrade with this purpose. In this speech, he insisted that the fundamentals of socialism could apply to African countries as much as they did to China and Cuba. In this international forum of youth politics, Machyo thus drew on a different set of alliances than he had in the context of East African networks in London.

Intellectual continuity: Ideas from Guinea

Decades later, in 1988, Machyo delivered a paper at Makerere. Despite being in a very different position with regard to the machinery of the state by this point, there is visible continuity in some of Machyo’s intellectual concerns. The paper was titled ‘Education as an instrument of development; Intellectual liberation as a pre-condition’. This linking of the cultural and economic spheres was something that Machyo had always insisted on, and had appeared in his pamphlets, such as Uganda: Riots Against Corruption and Exploitation (1960) and Africa in World Trade (1963). Specifically, both in these early pamphlets and the paper much later, Machyo quotes Sékou Touré, the first president of Guinea and one of the first to discuss the concept of ‘decolonising the mind’ in the 1950s. Even though Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o later popularised this idea in East Africa, Machyo continues to quote Touré in 1988, two years after Ngũgĩ’s Decolonising the Mind was published. While no hard conclusions can be drawn from this archival piecing together, this does illustrate the pervasiveness of the networks of African students that Machyo moved in, and the possibility of tracing ideas that carry all through thinkers’ lives, shaped by certain experiences, even as their political positioning changes dramatically.

Archives and online sources

- Murumbi Africana Collection, Kenya National Archives, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Library of the British Institute in Eastern Africa (BIEA) and Institute Français de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA), Nairobi, Kenya.

- Papers of the Movement for Colonial Freedom, SOAS, London, UK.

- ‘My life – my struggle’, biographical document, kindly shared by Peter Obanda Wanyama.

- Justice Patrick Tabaro, ‘Adios Mzee Chango Machyo’, The Observer, 22 October 2013, online.

- ‘Museveni hails Chango Macho as extraordinary’, New Vision, 22 October 2013, online.

Further reading

- Tajudeen Abdul-Raheem, Pan-Africanism: Politics, Economy, and Social Change in the Twenty-First Century (New York: New York University Press, 1996)

- B. Chango Machyo, Sulwe (London: 1961)

- B. Chango Machyo, Land Ownership and Economic Progress (Lumumba Memorial Publications, 1963)

- B. Chango Machyo, Aid and Neo-Colonialism (London: Africana Study Group, 1964)

- B. Chango Machyo, Africa in World Trade (London: Africana Study Group, 1964)

- B. Chango Machyo, Pan-Africanism (Makerere Adult Study Centre Pamphlets, 1968)

- B. Chango Machyo, Africa: Struggle for the Second Liberation : The Challenge of the 21st Century (Kampala: Lusamia Pub. Association, 2005)