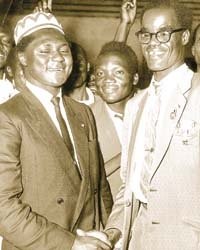

Arthur Aggrey Ochwada (1926-2013)

Pioneering trade unionist, founder of the Trade Union Congress of Kenya, and frequent rival of Tom Mboya

Ochwada was born in Samia in the present-day Busia county in 1926. He served in the British military in a non-combatant role during World War II; he spent time in India, Sri Lanka and Somaliland. On returning to Kenya he briefly worked as a teacher. A founder member of KANU and senior office-holder in the early years of the party before independence, he is best known as an MP and assistant minister from 1969 to 1974. His second wife was Lucy Nyokabi, granddaughter of Jomo Kenyatta, and Ochwada was the cousin of former Vice President Moody Awori.

Ochwada was defeated in 1974 election. He moved to Uganda following the return to power of Milton Obote, a friend from Ochwada’s days in the East African regional assembly in the early 1960s. Ochwada remained in Uganda until Museveni’s National Resistance Movement toppled Obote in 1985. Ochwada was also a friend of the South Sudanese leader, John Garang. The two men met in prison in 1963, when Ochwada was serving a sentence relating to his mismanagement of trade union funds.

Trade unions and the Emergency

Ochwada’s entry into politics and national prominence came about first because of his work in the trade union movement. He moved to Nairobi in the late 1940s and worked as a building sub-contractor, joining the union before quickly heading it. Ochwada’s East African Federation of Building and Construction Workers was part of a trade union movement ripped apart by the British campaign against Mau Mau. The start of the State of Emergency in October 1952 saw widespread arrests of trade union leaders, which in turn created a vacuum filled by a new generation of young, ambitious trade unionists such as Ochwada and Tom Mboya.

At first, Ochwada and Mboya were allies, albeit uneasily. They quickly became well known figures within Kenyan politics. In the absence of any nationwide political party for Africans until 1960, the Kenya Federation of Labour led by Mboya was the most important vehicle of African political involvement through much of the 1950s. Ochwada served as Mboya’s deputy and assumed control of the organisation in 1955 & 1956 while Mboya studied in the U.K. and travelled to the U.S.

The global Cold War and Kenyan labour

Ochwada travelled to the U.S. himself in 1959, training at Harvard and visiting numerous unions in the US to learn more about union management and collective bargaining. Like Mboya, he enjoyed a close relationship with a number of leading trade unionists in the U.S., most notably Maida Springer and Jay Lovestone of the AFL-CIO, the umbrella body for U.S. trade unions. Both first made contact with the AFL-CIO through the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, a worldwide, avowedly non-Communist organisation that was comprised of affiliates, such as the AFL-CIO and the British Trades Union Congress, across the Western world. The KFL’s forerunner had joined the ICFTU in 1952.

Through much of the 1950s, the ICFTU provided practical assistance, training opportunities to the KFL and acted as a form of international lobbying organisation on behalf of the KFL, particularly through the TUC in Britain around the arrest of union leaders in Nairobi during Operation Anvil in 1954. However, the Kenyans found the European influence on the ICFTU meant that too little attention was given to nationalism. The US-based AFL-CIO, however, was more willing to provide greater assistance to the KFL in the form of funds for Solidarity Building, other funding, equipment and the advice of key figures, such as Springer and Lovestone.

The interest of the AFL-CIO in the KFL was due to a number of reasons. First, through the 1950s, the AFL-CIO, a fiercely anti-Communist organisation, was concerned that the American government was allowing its policies towards the colonised countries of the world to be dictated by the European colonial powers. The leading figures in the AFL-CIO, including its president George Meany, were convinced that such policies would only serve to increase the likelihood of a growth of Communist influence. Nationalists angered by colonial rule would, Meany and others believed, turn to the Communist powers in order to get support if the U.S. continued to ignore them.

Second, the AFL-CIO had also become greatly involved in the civil rights movement in the U.S. after World War II and hence support for African nationalism seemed to be an obvious extension of that trend. At first focused on South Africa, the publicity given to the suppression of the Mau Mau rebellion attracted considerable attention in the U.S. and meant Kenya was in the limelight of any discussion of nationalism and liberation.

Third, the AFL-CIO’s leaders formed particularly close connections with Mboya himself. They viewed him as not just an important figure in Kenya but as a potential leader of a global movement that set out an alternative vision of freedom from that proposed by the more radical, left-leaning Afro-Asian group. This meant Mboya enjoyed great amounts of funding, both for his personal political campaigns and for the KFL more widely.

Once the Emergency was over in 1960, AFL-CIO backing was critical in the success of the KFL in heading off the challenge from disaffected unions in Kenya, who supported Oginga Odinga and the more radical position within KANU, but also supporting Mboya in his efforts to help lead KANU to victory in the pre-uhuru elections of 1963.

Ochwada’s global connections

Ochwada was, at first, happy to ride on Mboya’s coattails. His connections with the KFL and the ICFTU meant he undertook a huge amount of travel, attending conferences in Uganda, Tunisia and Ghana, including the All Africa People’s Congress in Accra in December 1958. He sat on international committees for both the ICFTU and the Plantation Workers Federation.

His enthusiasm for mobility, and that of Kenyans more broadly in this period, was rooted in the specific context of Kenya in the 1950s. The restrictions on movement imposed by the colonial government as part of the brutal counterinsurgency meant opportunities to escape the grip of the colonial security forces were eagerly embraced.

When in Kenya, Ochwada assumed a significant role within the KFL as Mboya’s responsibilities in the Legislative Council and international travel occupied more and more of his time. But as the AFL-CIO funding – never secret – became a matter of greater controversy within Kenyan politics, Ochwada sort to distance himself from Mboya.

Rivalry with Mboya

The two men had never been close friends. Ochwada had mistrusted Mboya from the very earliest days of them working together within the KFL and he was clearly envious of the global fame the much more charismatic, dedicated and skilled Mboya enjoyed. Although very much part of the relationship with the AFL-CIO, Ochwada turned against it and Mboya; accusing both of neo-colonialism. He set up a new body to rival the KFL, the Trade Union Congress of Kenya in 1960 – a splinter body which attracted great support from the pro-Odinga faction - before being expelled from the KFL. He and Mboya briefly reconciled – Ochwada served under Mboya as KANU’s general secretary – before they fell out once again. Ochwada’s legal problems then began; he faced trial on unrelated charges before being jailed for misuse of union funds.

Personal lives and global history

Ochwada’s life was certainly colourful and eventful. But it also reveals something about the ways in which the global politics surrounding the labour movement profoundly influenced the course of Kenyan decolonization. It also shows how important very personal relationships and emotions were to dictating events. Ochwada’s ties to the AFL-CIO leaders were initially very close; his correspondence with Springer full of, at first, great warmth and friendship and then, later, enmity. In other words, global history can be very personal history.

Archives and online sources

Ministry of Labour files at the Kenya National Archives

Collections of East African Standard and The Daily Nation at the McMillan Memorial Library, Nairobi.

Oscar Obonyo, ‘Ex-Minister and Uhuru’s Kin Passes On,’ The Standard, 20 April 2013,

Oscar Obonyo, ‘Ochwada’s Unfulfilled Dream,’ Daily Nation, 28 August 2005

‘Uhuru Mourns In-Law Ochwada,’ Daily Nation, 20 April 2013

Records of the AFL-CIO at the University of Maryland

Records of the American Committee on Africa at the Amistad Research Centre

Tom Mboya Papers at the Hoover Institute Archive

Records of the ICFTU at the International Institute of Social History

Further reading

Anthony Clayton & Donald Savage, Government and Labour in Kenya 1895-1963 (Frank Cass, London: 1974).

David Goldsworthy, Tom Mboya: The Man Kenya Wanted to Forget (Heinemann, London: 1982).

Clement Lubembe, The Inside of Labour Movement in Kenya (Equatorial Publishers, Nairobi: 1968).

Tom Mboya, Freedom and After (Little, Brown, London: 1963)

Yevette Richards, Maida Springer: Pan-Africanist and International Labor Leader (University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh: 2004).

Paul Tiyambe Zeleza, ‘Trade Union Imperialism: American Labour, the ICFTU and the Kenyan Labour Movement,’ Social and Economic Studies, 36, 2 (1987), 145-70.